We’re all seeking knowledge, even basic stuff like what’s the weather going to be so we can decide what to wear, whether to walk or drive to town. Or maybe knowing what’s in the food we are about to buy or eat. Beyond that knowledge is necessary for survival in a fast moving complex society that is so reliant on technology that for many of us is beyond our understanding, at which point it’s handy to know who to trust when it comes to product purchasing – and so on it goes. We take what we know for granted and we assume that others will be honest and not take advantage of our lack of knowledge, but it’s wise for us to include a degree of scepticism sufficient for us to detect when we’re being taken for a ride so to speak. As we consider the future for Munibung Hill it will be important that we listen to what ‘country’ is telling us, to understand the needs of the plants and animals living there. The knowledge holders of the geodiversity, the biodiversity, the cultural diversity, all need to be represented, such that the knowledge informs the decisions necessary for Munibung Hill to be given ‘rights of nature’ status.

In this article: What Aboriginal people know about the pathways of knowledge, Stephen Muecke, professor of creative writing at Flinders University, Adelaide, and a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities, proposes that a long and deep association with the land – call her ‘country’ – is essential. This requires us to become immersed in the source of knowledge as it is written and expressed in-situ – in and on the ground – rather than attempting to learn knowledge as we do by reading books and attending lectures or conferences. He begins by asking:

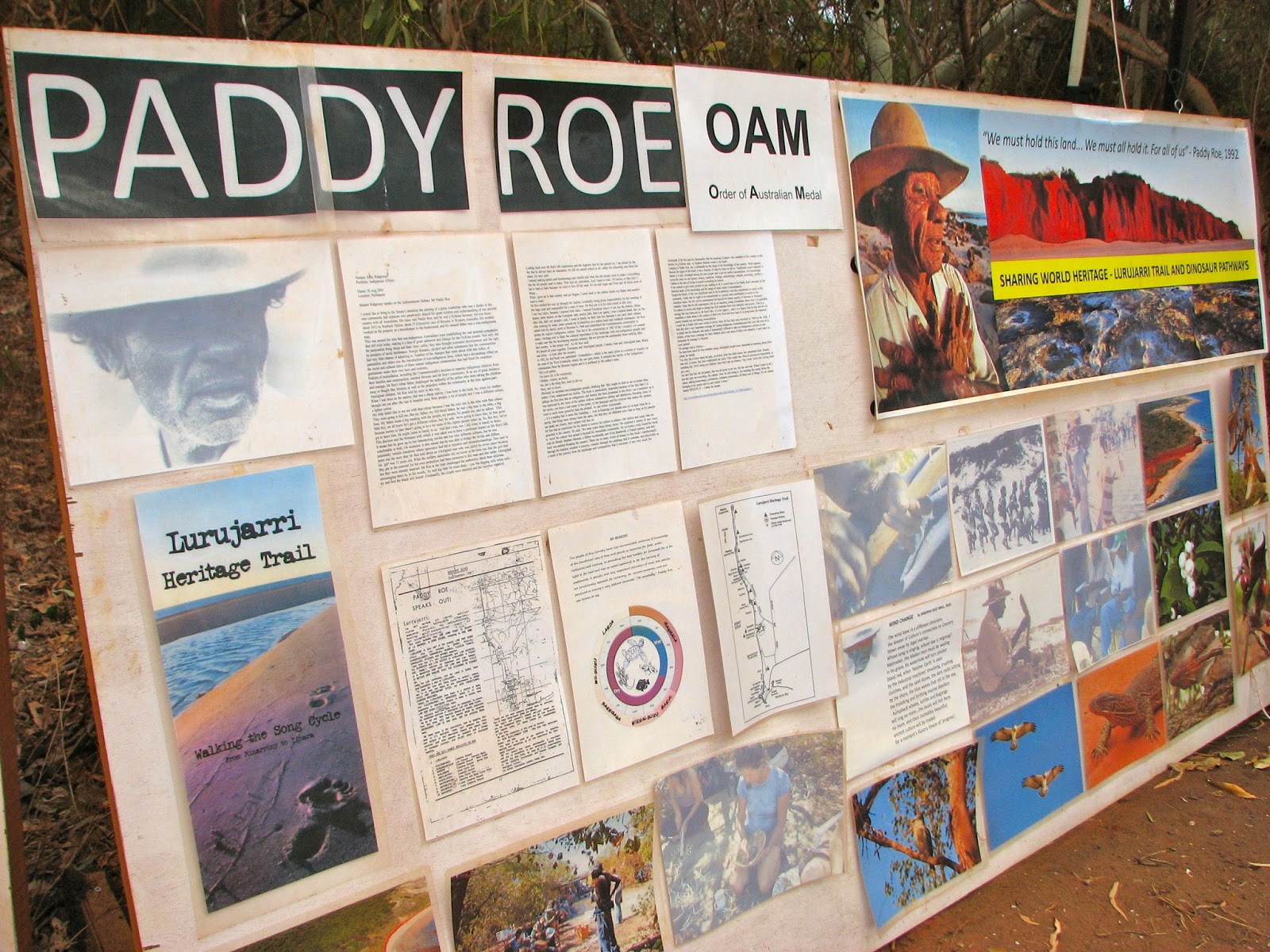

What can living in one place for 60,000 years teach a people? Walking with Aboriginal people in the far North-West of Australia has given me some idea. When I wrote the book Reading the Country (1984) with the Berber artist Krim Benterrak and the Nyikina elder Paddy Roe, we walked the world that Paddy was born in – what his people call ‘Country’. I found that the conceptual structure of his world was completely different to the Western one in which I had been trained. Not only was his knowledge not reproduced in books like the ones he nevertheless wanted to write with me, but it had nothing to do with authorship. Knowledge didn’t originate with individuals, and the concept of mind was irrelevant. Knowledge was on the outside; it was held in ‘living Country’. And humans had to get together to animate this knowledge.

And later …

If knowledges are environmentally embedded, and have to be activated through skilled practices, our orthodox idea that the privileged pathway for knowledge acquisition is cognitive, from one brain to another, is challenged. Think about it: we have never been able to ‘think’ without more-than-human extensions, such as Paddy’s finches, Galileo’s telescope, Newton’s apple, today’s world wide web. There might be specific tools, but there are also more extensive conducive environments: a teacher emphatically telling her pupils to ‘get this into your heads’ while the brightest of them is gazing out of the window. Learning happens only after pupils are interested, which means, using the Latin root again, that they ‘are between’ (inter-essere), that is, hooked into a heterogeneous network of relationships.

And later …

…. as this modernisation narrative hits the wall that is planetary finitude and environmental emergencies, new pathways are opening up for Indigenous knowledge transfer.

How do they get them [the moderns, the technology obsessed] to understand? How do they make their knowledge inspirational, as I asked at the beginning? You have to get out of your speeding vehicles, slow down to walking pace, and look around and see what needs to be kept alive. Each territory has its own nature, and living in that place teaches you that you are part of it: you breathe its air, drink its water and share its nutrients. And they compose your own living tissues in the same proportions. There is no escape; there is no better world. There is a song that teaches you this, now that you have taken the time to listen; it’s not just a matter of ‘putting your mind to it’ or accepting the facts. The Country has been singing this song for generations. I wish I could sing Paddy’s ancestors’ Dreaming song that makes the oysters grow fat – but this is not the time and this is not the place.

Stephen Muecke, is professor of creative writing at Flinders University, Adelaide, and is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. His most recent books are The Children’s Country: Creation of a Goolarabooloo Future in North-West Australia, co-authored with Paddy Roe (2020) and Latour and the Humanities (2020), edited with Rita Felski.