The place you feel most at home isn’t always the place you call home.

It’s an interesting thought. We talk about our houses as being our homes and yet when we are cooped up in them for too long we feel trapped and when of course we hear of people who have been confined to their rooms or houses for months or years on end, we call this a crime against their freedom to associate with other human beings let along the wider world.

So it is little wonder that many people see their house, their home, as a place to eat, raise a family and recuperate from a day’s work with a good nights sleep, but after that the reality is they feel more at home, not when in their house home but when in the natural world home, be that the garden, bush or the sea. That’s where, and that’s when, they feel most at home.

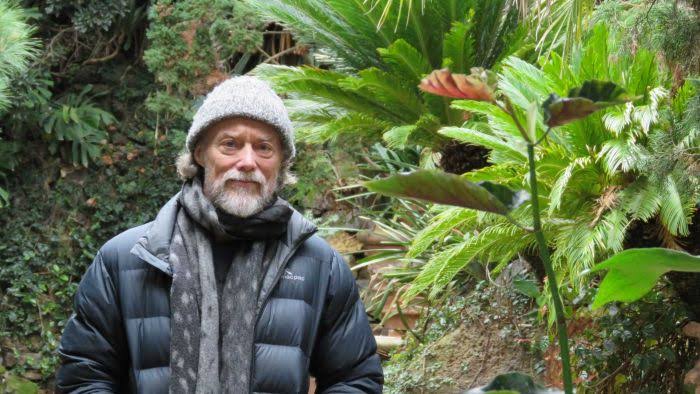

Bill Henson is one of Australia’s finest visual artists and photographers; he’s a master of light and an artist whose work’s complexity is masked by a deceptive simplicity.

The place you feel most at home isn’t always the place you call home.

It’s an interesting thought. We talk about our houses as being our homes and yet when we are cooped up in them for too long we feel trapped and when of course we hear of people who have been confined to their rooms or houses for months or years on end, we call this a crime against their freedom to associate with other human beings let along the wider world.

So it is little wonder that many people see their house, their home, as a place to eat, raise a family and recuperate from a day’s work with a good nights sleep, but after that the reality is they feel more at home, not when in their house home but when in the natural world home, be that the garden, bush or the sea. That’s where, and that’s when, they feel most at home.

Bill Henson is one of Australia’s finest visual artists and photographers; he’s a master of light and an artist whose work’s complexity is masked by a deceptive simplicity.

In this edition of a Sense of Place, he takes us back to Glen Waverley, where he grew up and explains how Rembrandt and Bach transformed the Australian landscape of his imagination.

He explains to Jonathan Green on Blueprint for Living (ABC RN): “… the destruction or disappearance of the landscapes of our childhood kind of forms a violence that we do to ourselves, the sense of continuity is lost – of culture still being inside of nature. I think this is being torn away. We are doing this to ourselves and it strikes me as a kind of violence. Home is at the heart of the real. If you want to weaken a people you move them around, so that nowhere is home. This turns us into fugitives in our own landscape. It’s a subtle thing, it’s incremental. Another tree gets cut down and so on.”

If you have a generation born into that impermanence that can’t draw on that memory, then what have we got. Where does that leave people? The book Landscape and Memory by Simon Schama addresses this subject very well says Bill Henson.

Art provides us the opportunity to have some empathy with the subject of the art. To empathise with the characters in the play …. it allows us to connect and be a part of, a sense of continuity and belonging.

Munibung HIll is a huge artistic canvass that includes so much more than rocks and trees and birds and mammals. This is a place that is home to these species, a place that was home to indigenous people for thousands of years and is home (as visitors) for many people of non-indigenous background today. Munibung Hill is a place where we can empathise with our cousin species and appreciate the art of nature in all her glory.