In his book Changing Tides: An Ecologist’s Journey to Make Peace with the Anthropocene, Alejandro Frid argues for a change in thinking about environmental management and our place as humans in the natural world. We may not be Indigenous to the land where we live, but we can follow the example of Plantago major—a plant species that is naturalized but not invasive.

“The descendants of settlers and immigrants can’t become Indigenous to the land where we live. But we can follow the models of coexistence,” writes Frid.

Indigenous peoples now are only 5% of the global population. If the remaining 95% of humans lack connection to place, chances are that future Earth will be grim.

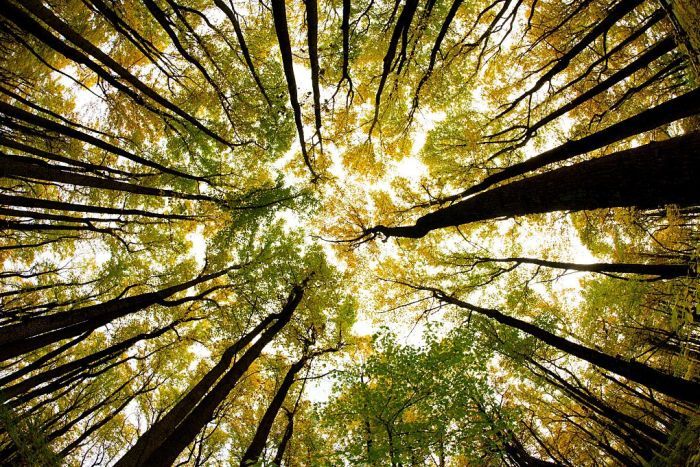

So how do we become part of the land on which we stand? Even if settler families arrived at their present countries several generations ago, it takes intentionality to become inseparable—spiritually, physically, viscerally—from the biodiversity that defines a coastline, a river valley, a forest, or any other landscape.

Plantain is a plant that is “so well integrated that we think of it as native.” Yet it is not. Plantain is naturalised: the term used for immigrants into a new country who “pledge to uphold the laws” of that specific part of the world.

Says Frid: “The likes of me will never become Indigenous; nor should we want to. But we can become naturalized, mindful and respectful of Indigenous laws. Those that, in the tradition of indigenous people, provide the ‘Original Instructions’ for practicing an ‘Honourable Harvest,’ one that promotes the diversity of life and the resilience of ecosystems.”

In this story: Alejandro Frid examines human impact on Earth in new book Changing Tides, by Anne Watson (National Observer, Reviews | April 24th 2020), we get to ‘listen in’ on an interview she conducted with Frid from his home office on B.C.’s Bowen Island on March 2, 2020. Frid said he is “aware of human potential to do better than we have so far.” He bases this optimism, in large part, on his work and experience with Indigenous peoples in a modern context.

Frid would like us to imagine a new story, to see ourselves as survivors. We must stop telling ourselves we are only capable of destroying our planet, he writes. Humans have, after all, survived for thousands of years. “This reinterpretation of ourselves is not mere fancy … rather, it is consistent with the world views and actions of Indigenous cultures that took shape millennia ago … and are still very much alive, integrating the traditional and modern, teaching others and learning from others.”

We must stop believing that burning fossil fuel equals prosperity, he writes. We should avoid jet flights, enact carbon laws that cut down on meat-eating, reshape land management, scrap fossil fuel subsidies, and price carbon for its actual damage to the planet. And we must change how we live, and think about how we live. For this, we need stewardship, wisdom, and common sense.

The inclusion of traditional Indigenous laws with modern laws, like the combining of science with ancient conservation practices, is yet another way to protect the environment. With traditional law comes a deeper respect for, and recognition of, the kinship between non-human species and humans.

“Indigenous peoples do not need the rest of the world to initiate their healing. What they do need is a just society that cares for the land, fish, animals and plants that make everyone whole. The question is whether the rest of us will choose to live up to our potential of widely practising reciprocity, with each other and with our non-human kin,” writes Frid.

Read more here: Changing Tides